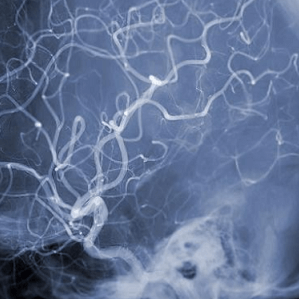

Cerebral aneurysms—those silent, blister-like bulges in brain arteries—affect millions, but not all communities face the same risks. According to the Brain Aneurysm Foundation, African Americans and Hispanics are more likely to develop brain aneurysms than white individuals. Women, particularly those over 55, also face a higher risk of rupture.

Dr. Scott Simon, a neurosurgeon at Penn State Health, likens an aneurysm to “a blister on a water hose.” Often undetected until a scan for another issue reveals them, these lesions can be fatal if they rupture. Half of all ruptures result in death, and two-thirds of survivors suffer permanent neurological damage.

Despite the severity, the causes remain elusive. “We don’t know,” Simon admits. While smoking and family history are known contributors, many patients have neither. The interplay of genetic and environmental factors is still being unraveled.

Symptoms, when they appear, can be subtle—pain behind the eye, vision changes, or facial numbness. But rupture can bring sudden, catastrophic consequences: seizures, loss of consciousness, or even cardiac arrest. A subarachnoid hemorrhage, the most feared outcome, carries a 40% mortality rate.

Preventive screening is not routine, but those with multiple affected relatives are advised to undergo imaging every five years starting at age 30. Still, for many, the first sign is the rupture itself.

As research continues, the unequal burden of aneurysms on minority populations underscores the need for targeted awareness and access to care.

See: “The Medical Minute: The dangers of cerebral aneurysms” (May 29, 2024)