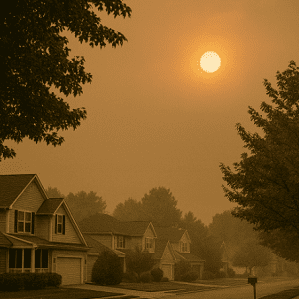

Wildfire smoke is becoming an escalating public health threat in America, with disadvantaged neighborhoods and communities of color bearing the worst of its impact. Recent wildfires in Canada poured hazardous smoke into the Midwest and Northeast, unleashing a wave of asthma, lung disease, and cancer risk that disproportionately harms people in low-income, urban, and segregated communities. The effects are compounded in urban “heat islands,” where lack of green space and concrete-dominated landscapes trap heat and smog, raising respiratory risks and adding to the daily dangers faced by residents.

For many, standard advice to “stay indoors” or purchase air purifiers and the best-quality masks is simply out of reach. Nearly half of U.S. renters spend at least 30% of their income on housing, and a quarter spend more than half, leaving little left for protective equipment or air conditioning. Without stable homes, an increasing number are forced to weather dangerous air outdoors, raising risks for the unhoused and for expectant mothers—who are then at greater risk of preterm birth and low birthweight babies. In the words of the report, “being unsheltered can also impact the youngest in our communities and determine their future health outcomes.”

Communities of color are overrepresented in these vulnerable populations due to a legacy of redlining, lower homeownership rates, and underinvestment. As climate change fuels longer, harsher wildfire seasons, advocates and researchers agree: addressing wildfire smoke’s toll requires affordable housing policies, better healthcare access, and a concerted effort to remedy structural and institutional health inequities.

See: “Wildfire smoke exacerbates health disparities” (September 12, 2025)