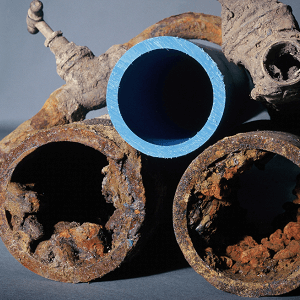

Chicago’s lead problem continues to be a significant health concern for its residents, particularly those living on the predominantly Black South Side. The city faces a daunting task of replacing an estimated 400,000 lead service lines, the highest number in any U.S. city. This issue disproportionately affects Black and Brown communities, making it a pressing environmental justice concern.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has given Chicago until 2047 to complete the replacement of all lead service lines, a timeline that has drawn criticism from environmental advocates. Chakena Perry, a senior policy advocate with the Natural Resources Defense Council, expressed concern about the extended deadline, stating, “That’s decades. That’s generations of children and adults consuming lead contaminated water.”

Lead exposure poses severe health risks, especially for children under six. A recent study found that nearly 70% of children in this age group in Chicago are exposed to lead in drinking water. Benjamin Huynh, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, described the extent of lead contamination in Chicago’s tap water as “disheartening” and unexpected in 2024.

The health effects of lead exposure are particularly devastating. As a powerful neurotoxin, lead can cause developmental and behavioral problems, fertility issues, and other health complications. These effects tend to be more severe in communities already facing social disadvantages such as poverty, further exacerbating existing inequalities.

The replacement of lead service lines is a complex and costly process. While some low-income homeowners may qualify for free replacements, others could face costs between $15,000 and $40,000. The city’s high percentage of renters complicates the situation, as current regulations only allow property owners to permit access for service line work.

Chicago’s lead problem is part of a broader national issue. Other major cities like New York and Cleveland also face significant challenges in replacing their lead infrastructure. The EPA’s ambitious plan to replace all remaining lead service lines in the country over a decade highlights the urgency of addressing this public health crisis.

The ongoing efforts in Flint, Michigan, serve as a cautionary tale for the challenges ahead. Despite seven years of work and $100 million invested, Flint’s lead line replacement program has slowed in recent years due to difficulties in locating remaining lines and obtaining necessary permissions.

As Chicago grapples with this long-term health hazard, the focus remains on accelerating the replacement process and ensuring equitable access to safe drinking water for all residents, particularly those in the most affected communities on the South Side. The city’s progress in addressing this issue will be crucial in safeguarding the health of its residents and reducing long-standing environmental inequities.

See “Chicago’s Lead Problem Isn’t Going Away Anytime Soon” (October 24, 2024)