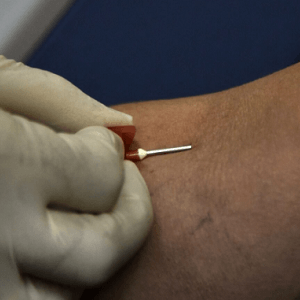

When physician assistant Jahidah La Roche arrived for a routine colonoscopy, the nurse quickly declared her veins difficult to access and attributed it to dehydration. La Roche knew otherwise. After requesting the nurse try her other arm, a vein became clearly visible and the IV insertion succeeded without issue.

This seemingly minor incident reflects a pervasive problem in American healthcare. La Roche explains that racial bias doesn’t always manifest as blatant discrimination but appears in small moments—a sigh, a glance, a provider who stops trying too soon. These interactions accumulate and shape how Black patients experience medicine, from routine procedures to critical situations.

Research reveals troubling patterns. In available literature, nurses cite “dark skin” more frequently as the reason for failed IV attempts than successful ones, even though darker skin doesn’t inherently make venous access harder. A 2023 survey found that 35% of Black adults reported unfair treatment or judgment from healthcare providers based on their race.

The consequences extend beyond uncomfortable blood draws. These bias-driven assumptions affect who receives adequate pain management, correct diagnoses, and serious consideration of symptoms. Many Black patients avoid seeking care altogether after repeated negative experiences. La Roche argues that implicit bias training alone proves insufficient. Medical institutions must incorporate practical bedside training on techniques for all skin tones as a core clinical skill, while healthcare systems need accountability structures with real-time feedback loops addressing bias-related complaints.

See: “Racial bias in medicine can be as simple as dismissing Black patients as a ‘hard stick’” (December 2, 2025)