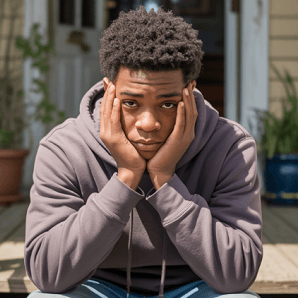

Black youth exposed to violence and danger in childhood face more than immediate trauma—they carry the burden into adulthood through accelerated aging and increased cardiac risk. A new study tracking 449 Black Americans from age 10 to 29 found that early exposure to danger predicted elevated alcohol consumption later in life, even among those who didn’t drink heavily as teens.

This delayed effect, called “incubation,” links childhood adversity to adult health problems through immune system changes. Researchers found that exposure to danger altered DNA methylation in FKBP5, a gene tied to inflammation. That change was associated with higher alcohol use at age 29, which in turn led to faster biological aging and increased cardiac risk.

The study’s lead author, Steven R.H. Beach, explains that these effects are independent of early substance use. “We found a significant incubation pathway from childhood danger to elevated alcohol consumption and then to health outcomes,” he writes. The impact was stronger for Black men in terms of alcohol use, but Black women showed greater vulnerability to its health consequences.

These findings underscore the long-term toll of structural racism and community violence. Black children are more likely than white children to witness beatings, shootings, and other traumatic events. The study suggests that these experiences don’t just shape behavior—they rewire biology.

Efforts to reduce health disparities must begin early, with safer environments and stronger support systems. Without intervention, the damage of childhood danger may silently unfold for decades.

See: “Childhood exposure to danger increases Black youths’ alcohol consumption, accelerated aging, and cardiac risk as young adults: A test of the incubation hypothesis” (July 16, 2025)