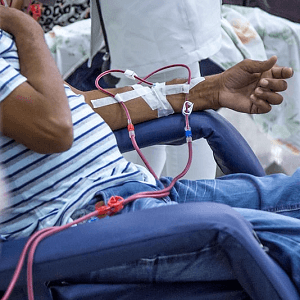

In the heart of Brooklyn, One Brooklyn Health (OBH) stands as a beacon of hope for some of New York City’s most vulnerable residents. Yet, as the safety net hospital system embraces a new race-free algorithm to assess kidney function, it faces a stark reality: changing one equation is just the beginning of addressing deep-rooted health disparities.

The removal of race from kidney function calculations promises to flag Black patients with kidney disease earlier, potentially saving lives. However, OBH’s experience reveals a more complex picture. Dr. Gilda-Ray Grell, a nephrology fellow, describes the challenge as “astronomical,” with an estimated 350,000 people in their service area potentially needing kidney care.

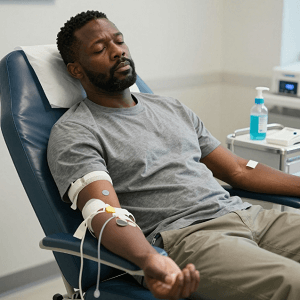

Despite this staggering number, OBH currently treats fewer than 2,000 kidney patients. Many arrive at the emergency room already in full-blown kiney failure, having never received crucial preventive care. Social problems, resource scarcity, and severe illness create barriers that a single algorithm change cannot overcome.

Yet, there’s hope on the horizon. OBH has partnered with NYU Langone Transplant Institute to make kidney transplants more accessible. A new diabetes center aims to prevent kidney disease before it takes hold, offering advanced technologies and flexible scheduling to accommodate patients’ needs.

Dr. Sandra Scott, OBH’s interim CEO, acknowledges the challenge: “There was a belief, we’re a safety net so we’re automatically doing health equity work. We’re not immune. There is structural racism baked into the system.”

As OBH grapples with these systemic issues, its staff remains committed. Nurses like Valencia Grant-Forbes go above and beyond, checking on patients even on Sundays before church. It’s this dedication that fuels the ongoing fight against health disparities in Brooklyn’s kidney care crisis.

See “A race-free algorithm is merely the start for a safety net hospital confronting an onslaught of kidney disease” (September 10, 2024)