Disease Disparities

Hispanic Cancer Survivors Face Higher Cardiometabolic Risks

Diabetic Retinopathy Rates Soar Among Young, Minorities

Language Barriers Hinder Rural Health Access for Non-English Speakers

Physicians Increase Screening for Patients’ Social Needs

Environmental Disparities

Air Pollution’s Mental Health Toll Higher in Redlined Areas

Climate Change Drives Health Disparities at US-Mexico Border

Air Pollution Drives High Death Rates in Black Americans

Disturbing Health Disparities

Health disparities are differences in the burden of illness, injury, disability, or mortality experienced by one group relative to another. These differences are closely linked with social, economic, or environmental disadvantages.

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF).

Treatment Disparities

Black Community Urged to Embrace Organ Donation Amid Health Disparities

Non-White Children Face Higher Risks in Cleft Lip Surgery Outcomes

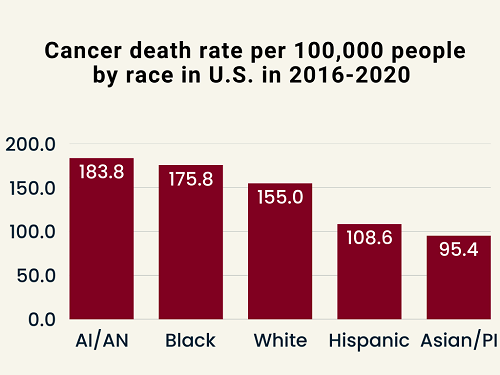

Death Rate Disparities

Cancer Death Rates Fall, But Disparities Persist

Homicide Widens Life Expectancy Gap Between Black and White Men

Racial Disparities Persist in U.S. Cancer Mortality Rates

Latest Health Disparity News

AA Template

Health Disparities Drain Wealth in Black Communities

Health Disparities Research Defunded Amid Political Shift

Cancer Patients’ Social Risks Often Go Undocumented

Parkinson’s Research Excludes Many Blacks, Hispanics and Asians

Redlined Neighborhoods Still Lack Emergency Care

Metabolic syndrome risks vary across Asian American communities

Unsettling Stories

News about health disparities among Hispanic Americans

Racial and Income Gaps Persist in Access to Free Preventive Care

Insurance Type Influences Hispanic Kidney Transplant Outcomes

HPV Awareness, Vaccine Rates Reveal Significant Health Disparities

Excess Deaths Highest Among Younger Minorities During COVID Pandemic

Hurricane Displacement Hits Black, Latino Communities Hardest

Mexican Americans Face Rising Liver Cancer Risk Across Generations

Mental Health Decline Worsens Disparities for Minority Adults

Study Finds Black and Hispanic Kids Face More Hospital Safety Issues

Disparity Disruptors: Individuals Working to Address Health Disparities

Lauren McCullough

Studies why Black women are more likely to die from most cancers and sooner

Vanessa Sheppard

Tackles Racial Disparities in Breast Cancer Care Among African American Women

Alyson Shirley

Develops culturally tailored health interventions that incorporate Native American languages and traditions

J.C. Abdul-Mutakabbir

Educates healthcare professionals about racial biases and health equity

Tamara Cadet

Promotes health equity in underserved populations in areas of HIV/AIDS and aging.

News about health disparities among Black Americans

Heat Wave Threatens Elderly Black Americans

Blacks with Diabetes Get Colon Cancer More Often

Stroke Treatment Delays Longer for Black Patients

Suicide Risk Underdetected in Minority and Male Youth

Genetic Risk for Kidney Disease Higher in West Africans

Pharmacy Closures Hurt Latino and Black Communities

Health Disparities Data

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) “Key Data on Health and Health Care by Race and Ethnicity” (June 11, 2024)

AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native

Source: American Cancer Society Cancer Facts & Figures 2024.

AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; Asian/PI = Asian American and Pacific Islander.

News about health disparities among Asian Americans

Geographic Factors Influence Heart Risk in Chinese Americans

Disaggregating Asian American Health Data Gains Momentum

Social Factors Widen Cardiovascular Health Gap in Asian Americans

Asian American Youth Face Higher Rates of Allergic Diseases

More Disparity Disruptors: Individuals Working to Address Health Disparities

Sinisa Dovat

Tackles Leukemia Disparities in Hispanic/Latino Children by Focusing on a Crucial Gene

Otis Brawley

Develops cancer screening strategies for effectiveness across diverse populations

Marcella Nunez-Smith

Promotes health equity, addresses systemic barriers, advocates for marginalized communities

Chandra Jackson

Investigates how poor sleep, influenced by noise, light pollution, stress overly affects minority populations

Wizdom Powell

Addresses mental health disparities, promotes health equity, advocates for social justice

News about health disparities among American Indians and Alaska Natives

New Medicare Drug Deal to Benefit Native American Elders

Native Americans Face Liver Transplant Disparities

Overdose Deaths Rising Among Black and Indigenous Americans

Tackling Tobacco Use in Native American Communities

Initiatives by groups to address Health Disparities

Medical College of Wisconsin

Increasing number of physicians focusing on underserved at-risk populations

Wayne State University School of Medicine

Expanding access to early detection and targeted treatments for breast cancer in Black women, including a focus on the social factors that influence health outcomes

Morgan State University

Launching $171 million center to combat health disparities

University of Pittsburgh

Starting EMBRACE Center to improve birthing outcomes for Black mothers and infants in Western Pennsylvania

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee alumni

Providing tuition, housing, training to prepare physicians to improve health outcomes in Milwaukee’s marginalized communities

Henry Ford Health

Bringing prenatal care directly into Detroit schools where infant mortality rates are significantly higher than national average

Sutter Health, a medical network in California

Launching mobile mammography to bring screening to underserved communities in Oakland

Mass General Brigham and La Colaborativa

Launching affordable healthcare initiative for Boston’s underserved residents

Hawaii’s Waimea Clinic

Integrating traditional Hawaiian healing practices with modern medical care to build trust and improve health outcomes

Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center

Addressing cancer disparities in Nebraska by focusing on precision prevention and key risk factors specific to the state

American Heart Association

Providing financial and technical assistance to companies in Minnesota focused on addressing health disparities within their communities

American Heart Association

Investing $210+ million in scientific research on health inequities and expanding opportunities for underrepresented groups in science and medicine

American Lung Association

Increasing biomarker testing among Black Americans

Racial Disparities Task Force

Addressing high rates of hypertension-related maternal mortality and illness in U.S. Black women

American Medical Association

Launching programs to increase understanding of social determinants of health

Black Directors Health Equity Group

Increasing number of Black individuals serving on medical boards, which shape healthcare policies and practices

Chicago Austin Neighborhood

Launching trolley tour to educate residents about local fresh food sources and promote healthier eating habits

Nashville Black Wellness Collective

Combining physical activities with community building and education within Black community

National Kidney Foundation

Raising awareness about kidney disease in Latino community, which is disproportionately affected

Islamic Center of Detroit

Offers free mental health services to Muslim community

City of Boston

Targeting three main causes of premature death among city residents

Medicaid

Improving cultural competence of health care providers to reduce biases and improve patient-provider relationships

New York’s Erie County Legislature

Launching new Office of Health Equity to address racial disparities

Michigan Public Health Advisory Council

Strengthening public health infrastructure and improving communication to rebuild community trust to tackle health disparities

Hawaii Department of Health

Strengthening its Maternal Mortality Review Committee to address factors contributing to maternal deaths

MyOme and Broad Clinical Labs

Supporting Southern Research Program to bring genetics-driven health insights to Alabama free of charge to address healthcare disparities

CME Outfitters, provider of accredited continuing medical education

Collaborating with National Black Church Initiative to increase diversity in clinical trials and enhance cultural competency among healthcare providers

Heartland Surrogacy, Iowa’s first surrogacy agency

Addressing critical reproductive health care disparities within Iowa’s Hispanic community.

CaringWire of Columbus, Ohio

Developing advanced analytics tools to predict health risks and outcomes based on social determinants to address potential health issues

More Health Disparities Data

Source: CDC’s “Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2022.”

(2024)

Spotlight on Health Disparities

In Arizona, English-only school segregation policies, systemic racism and xenophobic laws created stark mental health barriers for state’s Latino students, nearly half the state’s K-12 children. AZ ranks worst in the nation for having enough counselors to serve students.

In Arizona, English-only school segregation policies, systemic racism and xenophobic laws created stark mental health barriers for state’s Latino students, nearly half the state’s K-12 children. AZ ranks worst in the nation for having enough counselors to serve students.

See : “In Arizona, a legacy of English-only education, systemic racism and xenophobic laws create a mental health crisis among Latino students” (April 19, 2024)

The so-called “Hispanic paradox” of good health began to unravel once researchers started digging deeper into the diverse subgroups within the Hispanic population and found significant differences in cardiovascular risk factors among various Hispanic ethnic groups.

The so-called “Hispanic paradox” of good health began to unravel once researchers started digging deeper into the diverse subgroups within the Hispanic population and found significant differences in cardiovascular risk factors among various Hispanic ethnic groups.

See: “Nearly 50 years after research began, more questions than answers about Hispanic heart health” (October 1, 2024)

Though Asians comprise 50+ racial and ethnic groups, their health data are often reported as a single “Asian American” category, masking significant disparities in their communities. As a result, Asians are experiencing growing disparities from undiagnosed health conditions.

Though Asians comprise 50+ racial and ethnic groups, their health data are often reported as a single “Asian American” category, masking significant disparities in their communities. As a result, Asians are experiencing growing disparities from undiagnosed health conditions.

See: “Overlooked health issues that ‘need to be addressed’ in Asian communities” (August 27, 2024)

An average 55-year-old Black man has same biological age as a White man age 68, and a 55-year-old Black woman the same frailty of a White woman who is 75. This gap may explain disparities in economic outcomes such as disability, length of working life, and lifespan.

An average 55-year-old Black man has same biological age as a White man age 68, and a 55-year-old Black woman the same frailty of a White woman who is 75. This gap may explain disparities in economic outcomes such as disability, length of working life, and lifespan.

See: “Health inequality and economic disparities by race, ethnicity, and gender” (October 29, 2024)

A recent survey of 6,292 U.S. adults revealed that one in three Black women reported negative experiences with healthcare providers that led to worse health outcomes or reluctance to seek future care. Three in five said they brace for potential insults before appointments.

A recent survey of 6,292 U.S. adults revealed that one in three Black women reported negative experiences with healthcare providers that led to worse health outcomes or reluctance to seek future care. Three in five said they brace for potential insults before appointments.

See: “Five Facts About Black Women’s Experiences in Health Care” (May 7, 2024)

So-called “deaths of despair” in the United States have shifted dramatically from White Americans to middle-age Native Americans, who now have much higher death rates from alcoholism, drug overdoses, and suicide than middle-age Whites.

So-called “deaths of despair” in the United States have shifted dramatically from White Americans to middle-age Native Americans, who now have much higher death rates from alcoholism, drug overdoses, and suicide than middle-age Whites.

See: “Deaths of despair now highest among Black and Indigenous Americans” (April 11, 2024)

Recent reports about health disparities

AA Template

Poor health is costing Black Americans not only their lives but also their financial futures. Research highlighted in Rolling Out shows how chronic illnesses disproportionately affecting African Americans strip away billions in potential wealth, creating an underrecognized driver of economic inequality. Cardiovascular disease affects 60% of Black adults, a rate far above national averages. The toll is stark: Black Americans die from heart disease at rates 54% higher than whites, cutting off decades of earnings and preventing families from building generational wealth. Diabetes adds another layer of burden, with more than 12% of African Americans living with the disease compared with 7.4% of non-Hispanic whites. The costs are not limited to doctor bills—these conditions reduce energy, increase sick days, and force early retirements, depleting retirement savings meant to grow across generations. The ripple effects extend well beyond the patient. Families often see children struggle academically when parents are ill or acting as caregivers. Adult children may forgo promotions or leave jobs altogether to care for sick relatives. This cycle of diminished earning power locks entire families into economic vulnerability. The report stresses that preventive care, nutrition, and mental health support should be viewed as wealth-building strategies. Regular screenings, healthier diets, and community wellness programs could reduce costly chronic illnesses while preserving long-term earning power. As the piece concludes, investing in health is not simply a personal matter—it is a financial strategy essential to creating generational wealth in Black communities. See: “How poor health costs Black Americans billions in wealth” (August 15, 2025)

Health Disparities Drain Wealth in Black Communities

Poor health is costing Black Americans not only their lives but also their financial futures. Research highlighted in Rolling Out shows how chronic illnesses disproportionately affecting African Americans strip away billions in potential wealth, creating an underrecognized driver of economic inequality. Cardiovascular disease affects 60% of Black adults, a rate far above national averages. The toll is stark: Black Americans die from heart disease at rates 54% higher than whites, cutting off decades of earnings and preventing families from building generational wealth. Diabetes adds another layer of burden, with more than 12% of African Americans living with the disease compared with 7.4% of non-Hispanic whites. The costs are not limited to doctor bills—these conditions reduce energy, increase sick days, and force early retirements, depleting retirement savings meant to grow across generations. The ripple effects extend well beyond the patient. Families often see children struggle academically when parents are ill or acting as caregivers. Adult children may forgo promotions or leave jobs altogether to care for sick relatives. This cycle of diminished earning power locks entire families into economic vulnerability. The report stresses that preventive care, nutrition, and mental health support should be viewed as wealth-building strategies. Regular screenings, healthier diets, and community wellness programs could reduce costly chronic illnesses while preserving long-term earning power. As the piece concludes, investing in health is not simply a personal matter—it is a financial strategy essential to creating generational wealth in Black communities. See: “How poor health costs Black Americans billions in wealth” (August 15, 2025)

Physician notes about Black patients more likely to question patient’s sincerity or competence

Clinicians are more likely to express doubt in the medical records of Black patients than White patients, according to a new study published in PLOS One. Researchers analyzed over 13 million electronic health records from a large health system and found that notes about non-Hispanic Black patients were significantly more likely to contain language questioning the patient’s sincerity or competence. Terms like “claims,” “insists,” or “poor historian” were flagged by artificial intelligence tools as indicators of doubt. While fewer than 1% of all notes contained such language, Black patients faced disproportionately higher odds of being described in ways that undermined their credibility. Compared to White patients, notes about Black patients were 29% more likely to contain credibility-undermining language and 50% more likely to question their competence. The study’s authors say this pattern may contribute to ongoing racial disparities in healthcare. “For years, many patients – particularly Black patients – have felt their concerns were dismissed by health professionals,” they wrote. They argue that biased documentation can stigmatize patients and affect the quality of care they receive. The researchers call for medical training that addresses unconscious bias and for AI tools used in clinical documentation to be programmed to avoid biased language. They believe their findings represent “the tip of an iceberg” and hope to raise awareness of credibility bias in healthcare. See: “Clinicians more likely to express doubt in medical records of Black patients” (August 13, 2025)

Health Disparities Research Defunded Amid Political Shift

Hundreds of federally funded research projects aimed at understanding and reducing health disparities have been abruptly canceled under the Trump administration’s second term, sparking alarm among scientists and public health advocates. The National Institutes of Health terminated at least 616 projects focused on closing health gaps between racial and socioeconomic groups. Nearly half of the $913 million in canceled awards had been earmarked for disparities research, including studies on maternal mortality, chronic disease, and access to care in underserved communities.Many researchers say their work was cut not for lack of merit, but because it included terms like “race,” “gender,” or “equity.” Dr. Kemi Doll, a cancer specialist, said the message was clear: “We do not value health equity.” One study, canceled and later reinstated, aimed to train doulas to support low-income mothers postpartum. Another, still defunded, sought to understand why Black women face higher risks of adverse birth outcomes by tracking biological aging. “It’s like they erased the problem,” said Dr. Jaime Slaughter-Acey, who is now seeking donations to complete the work. Critics argue that such research benefits all Americans. Programs originally designed for Black mothers, like sending blood pressure cuffs home after delivery, improved outcomes across racial groups. While the administration claims to support “all vulnerable populations,” many fear that eliminating targeted research will widen existing health gaps. “Disparity programs ask the question: Who are we missing, and why?” said Dr. Georges Benjamin. See: “Trump Administration Scraps Research Into Health Disparities” (August 13, 2025)

Cancer Patients’ Social Risks Often Go Undocumented

A new study reveals that social determinants of health (SDOH)—such as housing instability, isolation, and economic hardship—are rarely documented in the medical records of cancer patients, despite their known impact on outcomes. Using data from over 50,000 adults with cancer, researchers found that less than 2% had any SDOH-related Z codes in their claims, even though those with Z codes had significantly higher rates of comorbidities and metastatic disease. Z codes are diagnostic codes meant to capture individual-level social challenges. Yet 54% of oncologists surveyed had never heard of them. Only 19% had used them, and many cited lack of reimbursement and unclear clinical guidance as barriers. “Physicians are more likely to document Z codes if they’re tied to payer reimbursement,” the study noted. The most common Z codes included “problems related to living alone,” “occupational exposure to dust,” and “psychosocial circumstances.” These codes were more prevalent among women and patients in states with high out-of-pocket medical costs. Despite endorsements from CMS and the American Hospital Association, Z codes remain underutilized, limiting efforts to address disparities in cancer care. Researchers stress that better documentation is essential to understanding how social risks affect treatment and survival. Without it, public health initiatives and predictive models lack the data needed to support vulnerable populations. The study calls for increased provider awareness, financial incentives, and integration of SDOH into routine care. See: “Documentation of individual-level social determinants of health among adults diagnosed with cancer in the United States” (August 12, 2025)

Parkinson’s Research Excludes Many Blacks, Hispanics and Asians

Parkinson’s disease affects people of all racial and ethnic backgrounds, yet clinical trials and research continue to exclude many of them. According to 2023 NIH data, only 4% of Parkinson’s trial participants identified as Black, 3% as Asian, and 4% as Hispanic or Latinx—numbers far below their representation in the U.S. population. This lack of inclusion has real consequences for diagnosis, treatment, and access to care. Black Americans are more likely to be diagnosed at later stages, missing chances for early intervention. Latinx patients are less likely to see specialists trained in movement disorders. These disparities are not biological—they stem from systemic barriers in health care and research. Richard Huckabee, a young Black man, spent nearly nine years being misdiagnosed before finally learning he had Parkinson’s. His symptoms were dismissed, misattributed, and worsened by inappropriate medications. “There is no excuse,” he said, “just because I… do not fit the typical PD profile of an ‘old white male.’” The NIH’s Strategic Plan for Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility offers hope, but enforcement is weak. Researchers can still receive full funding without including diverse participants or reporting who was studied. To close the gap, experts call for tying funding to accountability, engaging communities with culturally relevant outreach, and investing in proven programs like Dance for PD® in multiple languages. Without sustained funding and inclusive practices, Parkinson’s research will continue to leave behind those who need it most. See: “Closing the diversity gap in Parkinson’s research” (August 12, 2025)

News about pressing issues in health disparities

More diversity needed in clinical trials

Health Disparities Worsened by Clinical Trial Underrepresentation

Cancer Trials Exclude Many African, Middle Eastern Patients

Real-World Data Key to Boosting Diversity in Clinical Trials

Lack of Diversity in Respiratory Trials Hinders Care

Alzheimer’s Research Faces Racial Disparities in Clinical Trials

FDA Purges Clinical Trial Diversity Pages Amid DEI Ban

Do algorithms, Artificial Intelligence (AI), or race-based adjustments reduce or worsen health disparities?

AI and Medical Algorithms Perpetuate Racial Health Disparities

AI Chatbots Perpetuate Racial Biases in Pain Assessment

Health Systems Scramble to Comply with Anti-Discrimination Rule

Boston Children’s Hospital Stops Using Race in Medical Rules

AI Bias in Medicine Threatens to Widen Health Disparities

Fewer than half of hospitals test their AI tools for racial bias

Maternal health disparities need urgent attention

Black Maternal Mortality Rate Remains Alarmingly High

Postpartum Depression Rates Soar Among Minority Communities:

Black Women’s Fibroid Risk Linked to Maternal History

Maternal Syphilis Rates Soar, Reveal Stark Racial Disparities

Health disparities affect organ donation and transplants